Mahmood Sabzi

Biography and interview on Janet Rady fine art website which focusing on middle east fine art

BIOGRAPHY

Mamood Sabzi began painting at the early age of twelve. His love and talent for the arts was encouraged at an early age by an inspirational teacher and, more importantly, the enthusiastic support of his parents. He attended the University of Jundi Shapoor completing a Bachelor of Science degree in Agricultural Engineering. Like Joseph Beuys, whose works he studied in Germany, he believed that nature and its extended concepts were most relevant to arts and the concept of creativity, for as he has said, “The best part of agriculture,’’ he says, “is the purity of its primal space”.

In 1984 the ravages of the war caused him to move to Hamburg, Germany. For Sabzi, exile and freedom from his traditional muses represented a challenge which he assumed joyfully and enthusiastically. In 1991, Sabzi moved his family to Southern California, where he was excited by the dynamism of American Culture.

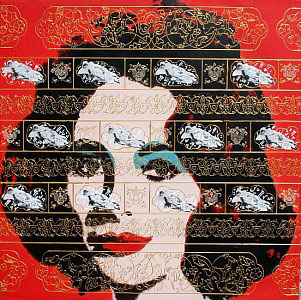

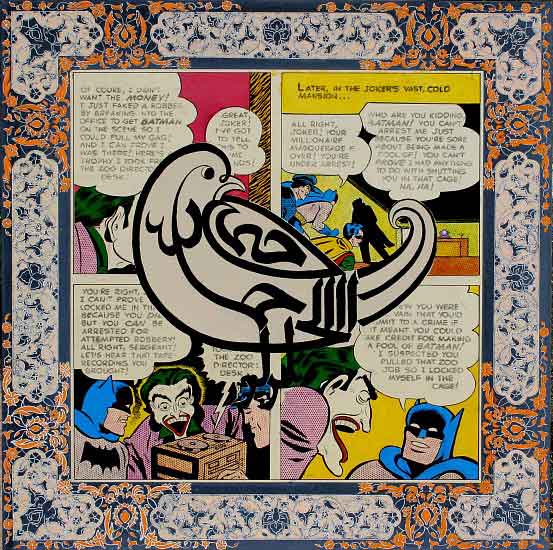

Sabzi’s paintings are lit by both eastern and western lanterns and philosophies. Persian miniatures, themselves inspired by metaphysical inspirations, serve as precursors for many of his forms. © Carlo Lamagna, Chair, Department of Fine Arts, New York University.

His works are in the Museum Permanent Collection of The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) U.S.A; Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA) IRAN and are also held in private collections in United States, Germany, France, and Japan.

INTERVIEW WITH MAHMOOD SABZI

July 20, 2016

By Art Journalist and Writer Lisa Pollman

You began to paint at an early age. What or who were your early influences? How did they shape your early work and your later pieces?

The first person who taught me about art was my elementary teacher, who was a very good painter and was inspired by the Impressionists. I began painting and playing music when I was twelve years old. As was customary with many Iranian families, I was encouraged to pursue something useful, so I received a degree in Agricultural Engineering from the Jundi-Shapour University in 1971 — however, I want to point out that my parents were very passionate about art and did support my journey to become a painter.

Did your move to Germany in the 80’s influence you and your work. How?

Despite working in another occupation, I found it difficult to stay away from my passion, which was painting. So in 1981, I moved to Germany to study art – particularly modern art. It was here that I began to develop my own style. I was deeply influenced by several European artists. Still, the Iranian traditions continued to populate my work.

Paul Klee had an influence on my work and in particular my abstract works, which were completed under profound emotional charges and stress. These works were mostly done without thinking but I felt every colour and form deep in my heart.

Did the separation from your homeland provide you with a clear lens in which to examine your Iranian heritage?

My happiest times in Germany were spent in museums. I often went from gallery to gallery in Hamburg and other German cities. However, the memories of my homeland mixed with the music that had infused my soul, produced an emotional and highly personal style that also addressed my pain of separation from Iran and my culture. This produced a mixture of memories of my Iranian experience with the pain of recreating myself in a new land that emerged on my canvases.

You often combine Eastern and Western elements. Are there any Western images in particular that you find interesting? Which ones?

In the early years of the 21st century, my memories of my homeland returned in a different guise. Suddenly the Qajars became a symbol of Iran’s modernity and also its failed dreams. Iran was a mixture of East and West and I found it amusing, while also being conflicted and painful. I found an emotional and intellectual remedy for my feelings in the photography of Antoin Sevruguin.

To me, his photographs of Qajar women were fascinating. Why? As I look back, I realise that their ease and self-conscious posing had evoked in me a sense of Iran’s history that I emotionally recognised. The women represented in Sevruguin’s photographs had a sense of pride in their femininity and in spite of the control exerted on them, they were in so many ways modern and liberated. I guess, to put it differently, what we had for so long seen as backward and primitive suddenly had become a symbol of liberty not only for women but for the country as a whole.

The Qajars after so much historical change and historical surprises turned out to be more progressive than we had originally viewed them. And more so, these Qajar women stand in sharp contrast to my western icons of Marilyn Monroe and many others. This contrast is quite significant as it not only distinguishes but also acknowledges the similarities amongst us all.

My world is split and yet unified. My dreams are of a homeland that I crave to rediscover and also of the painful knowledge that time has changed my world beyond recognition.