The house of ceramic, Glorification of clay and soil

Javid ramezani: “It is said that amount of digging underground in Iran During last 3000 years of human civilisation equals all the excavations man did in the hole planet earth.

Our ancestors enshrined the earth and this roots into our archetypic behaviour and individual culture.

All around geographical and cultural frontiers of Iran, a decadence and dissolution of history as well as loosing benefits of past Civilisation could be seen. One of these indexical points is Kashan which had been the center of ceramic in Iran from millennials B.C up to Safavid dynasty.

Iranian people choose ceramic as their very first base for drawing and transfering their thoughts and during the years this had made an information system and written language.

Today valueble effort of such hard working people as Dr. Abbas Akbari regenerates the forgotten Civilization of Sialk and Niyasar feilds.

Reclaimation of old houses is the reclamaition of a historic architectural style that is the contemporary poeple’s solution for returning to the values and sanctity of working and repairing the relationship between man and nature and all this, is the achievements of this Kshan’s renaissance.

I was trilled to see the Old texture of Kashan is reborn. Beside this, stablishing cultural places like ceramic House of Kashan raises the hope for vitilization of concerns about truth and aesthetics and not only economical purposes like building Hotels, Hostels and tourism industry is still alive in this ancient city.”

The House of Mud

Many thousands of years ago, there was a sea in what is at present the desert known as the Dasht-e Kavir; to its west now runs the road linking Qom to Keman. When the sca dried up, a salt lake was formed, surrounded by a sedimentary plain. Human settlements appeared on the narrow fertile strip situated between the mountains (to the west) and the desert (to the east), Tappe Sialk is one of these settlements, now located between the Garden of Fin and the old town of what has become Kashan.

In ancient times, Tappe Sialk looked like a walled stronghold, whereas it appears today as a mound of mud. Indeed, the mound was formed over more than five thousand years, by the accumulation of strata of mud-brick constructions. Mud is definitely the key-word! It was formed over millennia of alluvial deposits. We can handly imagine a more humble material; yet in the hands of craftsmen, it can be transformed into a world of wonder.

Indeed, already in the fourth millennium BC, the inhabitants of Tappe Sialk built their houses out of mud, and they used to decorate their walls with ochre pigments. During this early period they also became experts in the making of astonishing ceramics. These were clay wheel-formed vessels, fired in hearth furnaces and painted with reddish slip designs representing geometriscd animals and humans. The material was close at hand: it is a very fine kind of clay, somewhat pale yellowish in colour. The area around Kashan is also known for a series of mineral deposits; some of these ores were already used in these times for painting the walls, while others were used as slip-pigment for the vessels.

Water was also available, then generously flowing from the mountains; a spectacular waterfall can still be admired at Niyasar, west of Kasban.’ Water was also, from very remote periods, obtained through subterranean canals known as qunat. One of them still flows today next to the Garden of Fin, thus watering this wonderful area.

In the epoch of the Sasanian kings, the Kashan region was probably flourishing, since at least two fire-altars (uteshkardeh) are still to be seen at Talar-e Niyasar and Khorram Dasht. Early European travellers, such as Marco Polo, affirm that the Magi mentioned in Matthew’s Gospel came from Kashan. Persian-writing medieval chroniclers, for their part, suggest that the city was founded by Zubaida, Harun ar-Rashid’s wife, in the early 9th century CE. During the Buyyid (932-1062 CE) and Seljuk (1029-1194 CE) periods, Kashan grew substantially; a rare monumental witness of this period is represented by the minaret of the Old Friday mosque. This all-brick monument is dated 466 H/1073 CE by an inscription also mentioning the names of its patrons. Another remain from these times is the amazing octagonal fortress of Qal’e-ye Jalali, founded by the Seljuk sultan Malekshah, and entirely made of mud-bricks. The fortress is now much altered and also contains other later traditional mud-brick buildings, such as ab-anbar (water reservoir) and yakhchal (ice-pit). These kinds of traditional constructions, which can be observed all over the Iranian plateau, are perfectly adapted to the climate of arid lands. They are a matter of amazement, both because of the pure beauty of their architectural lines, but also for their incredible resourcefulness.

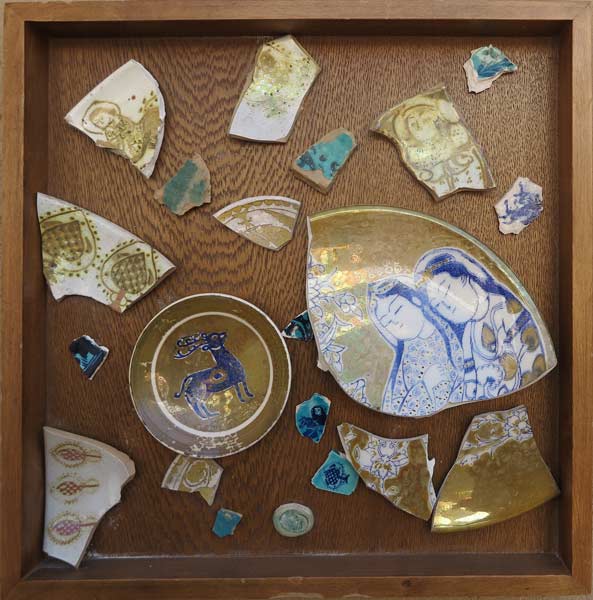

It was during the last decades of Seljuk rule, in the second half of the 12th century CE, that Kashan became the capital of Persian finest ceramics. These were the result of a series of experiments, concerning both the clay for forming the body of the vessels, and the decorative processes. Indeed, this period is marked first of all by the apparition of stone paste. This is made by mixing about 80% silica powder (either pure ground quartz or mixed with soda, thus forming a frit), with 10 to 20% of white clay. Most of the materials were available in the Kashan area; indeed, in the early 14th century CE, Abu alQasem mentions stones and clays collected at the nearby Fin area, and up to the village of Qamsar, about 40 km in the mountains west of Kashan.

A series of moulded large cups, all signed by a certain Hasan al-Qashani, probably testify to the early stages of stone paste wares; some of these whitish glazed objects are only slightly coloured with stains of cobalt, whereas others are completely painted with this hue, known as lajevardi in Persian. ‘ Cobalt oxides were also collected at Qamsar, although Abu al-Qasem mentions ores coming from Europe, too. The cobalt of Qamsar continued to be mined until the early 20th century, and its market distribution was in the hands of the well-named Lajevardi family.

During the late Seluk period, the technique of lustre painting appeared in Persia; the oldest dated artefact known to this day is a bottle housed at the British Museum and inscribed with the date Muharram 575 H./June 1179 CE. Contemporaneous with this technique, we find also a series of vessels decorated with the so-called mina’i or polychrome low-fired pigment process. At the turn of the 12th -13th centuries, the ceramics of Kashan became thus the epitome of the finest wares in the Iranian world. This position was maintained up to the middle of the 14th century, allowing the production of major works of art such as the monumental lustre mihrab-s made, among others for the shrines of Mashhad and Qom, but also for the Maidan-e Sang mosque in Kashan; this is now housed in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

The making of lustre ware follows a complex process; it is still very difficult to ascertain how the technique reached Iran. What we know for certain is that by the very end of the 12th century, an expert on rarities and precious stones named Mohammad alJowhar from Nishapur wrote the first known treatise on lustre making, forming a chapter of his book on precious stones, metals and exotica o More than a century later, in 1300, another Persian text described this technique again, although in a much more summarized version. This renowned text is Abu al-Qasim’s “treatise”, actually a short “conclusion” to his book on stones and perfumes.”

Excavations made in the city during the 1930’s have yielded some remains of the potters’ districts, unveiling traces of workshops and kilns. These were located in the areas of Malckabad, Kalahar, and Darb-e Zanjir. Unfortunately, most of these remains were lost a long time ago.

In fact, the Kashan ceramic industry declined during the following centuries; in the course of the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722 CE), Kerman became the major centre for ceramic production. Still, Kashan retained special attention from Shah ‘Abbas, who built the Garden of Fin, and was later buried in one of the city’s shrines. Instead, in the course of the Safavid era, Kashan’s major industry became carpet-weaving, which is still today one of its major glories.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Kashan was the abode of great families, such as the Ghaffari, the ‘Abbasian, the Borujerdi or the Tabataba’i. The glorious Ghaffari family gave birth to several great artists, among whom the painters Sani’ al-Molk (1795-1860) and Kamal al-Molk (1846-1941). All these families had their mansions built in the city, each one competing to be the most impressive in matters of bold architectural forms and astonishing decoration. Yet, these houses are still mostly made of mud, and possess all the typical devices of these kinds of buildings: strong walls lined with kah-gel (a mix of mud and straw), separate entrances for men and women, inner courts with gardens and fountains, vaults and cupolas pierced by tiny windows, bad-gir or “wind-towers” for aeration, and a semi-subterranean sardabe or cool-room. Fortunately, some of these great Kashani mansions are today being well protected and beautifully restored.

Even if modern Kashan appears these days as a somewhat small province-town, this does not mean that it has lost its past attraction. Indeed, among the contemporary artists from Kashan, mention must be made of Sohrab Sepehri (1928-1980), the celebrated poet and painter. To some extent, he continued a long time tradition that made Kashan the city of poets such as Muhtasham (1500-1588 CE) or Kalim (1581-1651 CE).

Therefore, it is not a complete surprise if the artist and potter Abbas Akbari has chosen Kashan for residence, where he is now a faculty member at the Architecture and Arts School of the Kashan University.

Among his many skills, he has been experimenting in the field of lustre ware making for several years now, thus reconnecting with the ancient art which made the glory of Kashan. He has studied the ancient texts on these matters; but he has also added new processes in the making of these forgotten techniques. His creations include, among many others, the extraordinary series of variations on the Maidan-e Sang Mosque mihrab, together with experiments combining metal and lustre ware.

Morcover, he now has the opportunity to restore an old Kashani house which is to become the abode for ceramics, in a celebration of mud and clay, through both ancient works and new creations. Assuredly, this will be the occasion for recuperating the memory of forlorn techniques and know-how. Indeed, the restoration of this house is to be achieved using the traditional materials and forms of local architecture, but it will also be the occasion for some new doubtlessly outstanding creations. This is really a matter of satisfaction and pleasure!

Yves Porter, Aix Marseille Université (France)

Regards

I am Syeda Rabia ceramist/educator from Pakistan .I am really interested to come and work in Iran in with ceramic artist. Please email me if House of Clay has residency for an artist.I want to share my work as well . Please email me where can I send it.

Dear Seyda Rabia,

We are not aware of House of Ceramic’s programs but we can ask for their email therefor you can ask them yourself directly.

we will email you as soon as we get the email address